In its 21st century guise of ‘anti-Zionism’, antisemitism makes use of a variety of weapons in its attempts to delegitimise the Jewish state of Israel. One of these weapons is to deny the historical connections between the modern Jewish people and the ancient lands in which their ancestors lived, much of which now constitutes the state of Israel.

This propaganda of denial is especially evident in the manner in which Palestinian propagandists and their supporters in the West speak of the four traditional holy cities of Judaism – Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias – as if they were Arab cities whose links with the Jewish people had never existed. On 29 June 2021, Palestinian Authority prime minister Mohammad Shtayyeh declared in a public address that “there is no connection between Israelis and the Jews, descendants of Jacob”, rather [the former] are the “Khazar Jews” who converted to Judaism in the 6th century CE.

https://www.memri.org/tv/palestinian-prime-minister-mohammad-shtayyeh-israel-jews-khazars

Second only to Jerusalem as a holy city of Judaism is Hebron. And second only to the efforts to deny Jewish connections to Jerusalem are those aimed at doing the same in respect of Hebron. The city is often presented in the international media as a microcosm of the entire Israel-Palestinian conflict. In the narrative favoured by these media, the very presence of 700-800 Jewish ‘settlers’ there, surrounded by a Palestinian Arab population of about 220,000, makes it a ‘flashpoint’ city. There the tensions generated by Israel’s ‘occupation’ and Jewish homes supposedly clash with Palestinian national aspirations.

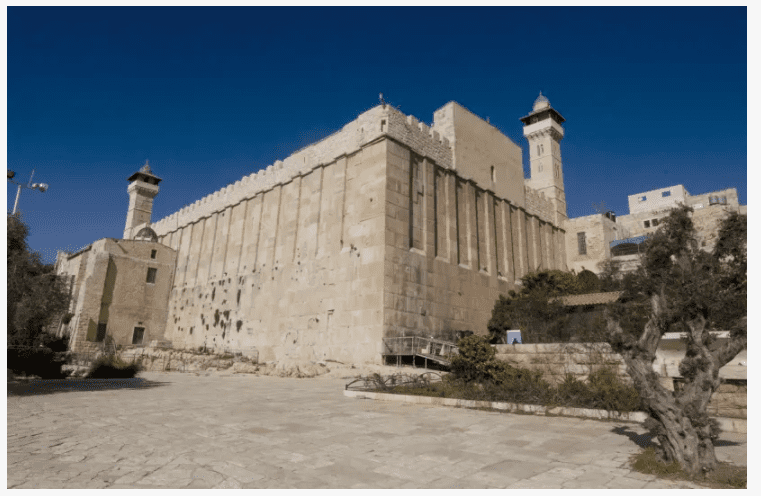

Hebron sits in the Judean hills 28 km south of Jerusalem at an altitude of 930 metres above sea level. For a thousand years it was part, first, of the independent kingdom of Judah, and later of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Judea, until the Roman empire put an end to Jewish autonomy in 135 CE.

The city contains the Cave of the Patriarchs, the site where, according to the Book of Genesis, Abraham purchased a burial plot: ‘Abraham buried his wife Sarah in the field of Machpelah near Mamre which is at Hebron…’ (Genesis 23). Abraham, his son Isaac and grandson Jacob and their wives share the same tomb. Since Abraham is an important figure in Islam and in Christianity, this makes the site holy not just for Judaism but for all three monotheistic religions.

King Herod the Great (d. 1 BCE) built a massive rectangular enclosure over the cave which still stands. The Byzantine Christian empire roofed in the enclosure and built a basilica which changed hands between Muslims and Crusaders, alternating between a church and a mosque, over the centuries.

The modern Jewish presence in Hebron goes back at least a thousand years. In 1166, during the period of Crusader rule, the great Torah scholar Maimonides came from Morocco and wrote, “On Sunday, 9 Marheshvan (17 October), I left Jerusalem for Hebron to kiss the tombs of my ancestors in the Cave. On that day, I stood in the Cave and prayed, praise be to God, (in gratitude) for everything.” A few years later, the Spanish Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela visited the site, noting that “this was a Jewish place of worship at the time of the [earliest] Mohammedan rule”.

After the Muslim reconquest of the area, the Mamluk and later Ottoman rulers forbade Jewish access to the site, allowing them to approach only as far as the seventh step of a staircase leading to one entrance of the enclosure. Things stayed that way for 700 years.

Jordan’s illegal occupation of Judea-Samaria (the ‘West Bank’) in 1948 brought all Jewish habitation in Judea to an end (it had already ended in Hebron after the massacre of the Jewish community in 1929). But with the Israeli victory in the Six Day War of 1967, Judea, including Hebron, suddenly came under Jewish control for the first time in 1,900 years and the humiliating restriction of Jews to the seventh step was lifted (the staircase being demolished). Jewish settlers were keen to return to the city.

Given the sensitivity of the Hebron site and other nearby holy places, Hebron was not included in the Oslo Accords of 1993-95 under which the major West Bank Arab population centres came under the control of the new Palestinian Authority (PA). It was dealt with separately in the Hebron Protocol, agreed between Israel and the PA in January 1997.

For security purposes, the city was divided into two areas, H-1 (80 per cent of the city) and H-2 (20 per cent, including the Old City). H-1 is under Palestinian civil and security control, while H-2 is under Palestinian civil control and Israeli military/security control. The Jewish settlers are concentrated in two locations in the Old City within H-2.

As for the Cave itself, the Israeli authorities allow the Islamic waqf (trust) to control and maintain most of the compound. To placate the waqf, Jewish access is limited to ten days each year, including the commemoration of Sarah’s death and Abraham’s purchase of the site.

Despite these tolerant arrangements, Israel’s very presence in Hebron is a trigger for hysterical allegations by Palestinian Arabs of Israeli conspiracy. Only last week, the construction of a wheelchair ramp to the Cave by the Israeli authorities was denounced as the latest evidence of ‘apartheid’ (though the ramp is accessible to both Arabs and Jews) and a plot by Israel to abolish the waqf and take complete control of the site. It has also become a particular target for international (and some Israeli) NGOs, who cast it as an obstacle to peace and accuse Israel of breaches of the Geneva Convention and international law.

Although the behaviour of some settlers can be aggressive and provocative, the real objection is to any Jewish presence at all. Ironically, those in the West most likely to label the latter as ‘illegal’ and obstructive to a future Palestinian state are those generally most in favour of ‘open borders’. A large section of western opinion has internalised the Islamist mindset that a Palestinian state must be Jew-free.

It is clear that Israel’s military presence in H-2 is necessary to protect the lives of the Jewish settlers from Arab Muslim violence. If the will for coexistence were there, the IDF would not be needed. This sad fact is borne out by the history of the city – a history largely peaceful but punctuated by intermittent periods of attacks on the Jewish community over the centuries, to which we will return in Part 2.

By Dermot Meleady