Stefan Zweig's life encapsulated the good times for Austria-Hungary’s Jewish community which spanned approximately the length of a human lifetime, the 71 years from 1867 to 1938.

Eighty years ago today Stefan Zweig, the chief chronicler of Vienna’s Jewish ‘golden age’, died by his own hand in Brazil. His life and death encapsulate the tragedy of Austria-Hungary’s Jewish community, whose good times lasted approximately the length of a human lifetime, the 71 years from 1867 to 1938.

Centuries of precarious Jewish existence punctuated by persecutions, massacres and expulsions came to an end with the Edict of Toleration issued by Emperor Joseph II in 1782. However, this withheld certain rights such as ownership of land and the right to build synagogues, and several of its reforms were reversed by Joseph’s successor. With the inauguration of the dual monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1867, the constitution promulgated by Emperor Franz Joseph I gave full emancipation to the Jews for the first time.

Jews now possessed full rights of citizenship alongside all the nationalities of the far-flung empire. Until then, they had lived mainly in the impoverished rural provinces of the empire – in the Czech lands, Hungary, Galicia (now divided between Poland and Ukraine) and Bukovina (now divided between Romania and Ukraine). With emancipation, Jews immediately began to pour in large numbers into the prosperous heartland of Austria, and especially to the city of Vienna.

In 1857 there were only 2,617 Jews in a city of nearly half a million, making up 1.3 per cent of the population. Within two years of emancipation, their numbers had grown to 40,277, and by 1890, to 99,000 or 12 per cent of the population. The peak was reached in 1923 when Jews totalled over 200,000, a minority of 10.8 per cent in a city population of 1.87 million.

The relatively small numbers understate the impact made by the Jewish arrivals on the life and culture of the city. Within a short time, their high levels of literacy and thirst for education ensured the entry of many Jewish citizens into the professions. Soon, they were succeeding in the fields of science, medicine, law, philosophy, business, economics and the arts.

Vienna was a city in which the arts and culture played a very significant role in civic life. Theatre reviews, rather than political or business news, were often the first items read in the morning papers. However, unlike their predecessors, the Habsburg aristocracy had ceased to play its historic role of patron of the arts. Whereas Mozart could discuss his operas with Joseph, Franz Joseph had no interest in music.

The vacuum was filled by the new Jewish citizens, who became enthusiastic supporters and consumers of Viennese culture. Excluded from the upper social circles of the imperial administration and the army, they could yet feel themselves on an equal footing with their fellow-Viennese in the cultural realm. They soon began to fill the concert halls and theatres, to visit exhibitions and to spend their money on books and pictures.

Within a generation, they were making their own original contribution, not only to the arts but to the intellectual life of the city in general. Much of what came to be admired around the world as a rejuvenated Viennese culture was the creation of the Jewish newcomers. Stefan Zweig, born in 1881, himself a product of that Jewish blossoming, a novelist, biographer and playwright, summed up its origins: ‘Because of their passionate love for the city, through their desire for assimilation they had adapted themselves fully, and were happy to serve the glory of Vienna.’

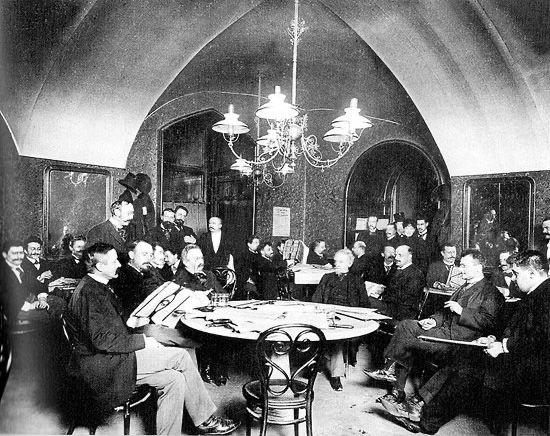

The Wiener Moderne movement, at its peak between 1890 and 1910, was a group of non-Jewish and Jewish figures who pushed out the boundaries of disciplines such as philosophy (Wittgenstein), architecture (Adolf Loos) and art (Gustav Klimt). The leading Jewish contributors included Sigmund Freud who revolutionised psychology, the composers Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg who pioneered new forms in late Romantic music and the modernist writers Arthur Schnitzler and Peter Altenberg, both prominent in literary circles along with the satirist and critic Karl Kraus. The prodigy Hugo von Hofmannsthal, a Catholic of Jewish descent, was acknowledged as the best poet of the movement. The city’s coffee houses where these figures gathered was the site of the gestation of many of the new ideas, giving birth to the famous Viennese ‘café culture’.

In reaction to this Jewish flourishing there arose a strong antisemitic movement. Its two leading figures were Georg von Schönerer (born 1842), a pan-German nationalist whose goal was the end of the multinational empire, and whose thug gangs beat up Slavs and Jews, and Karl Lueger (born 1844), founder of the Christian Social Party who, as Mayor of Vienna, brought in discriminatory practices against Jews in education and the city administration. More of an opportunist than the avowedly racist von Schönerer, Lueger kept Jewish friends, saying famously: “I decide who is a Jew”.

Into this social and political ferment stepped the young Binyamin Ze’ev (Theodor) Herzl, born in Budapest in 1860, emerging from the University of Vienna in 1884 with a doctorate in law. Of mixed Ashkenazi-Sephardic lineage, he was strongly Germanophile and a believer in Jewish assimilation. Beginning as a playwright, he became a journalist for the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse. Having already encountered antisemitism at the university, he met it again in more virulent form when he was sent to Paris in 1894 as his paper’s correspondent there.

French opinion was galvanised by the collapse of the Panama Canal Company, the financial scandal of 1892. The corrupt involvement of certain Jewish businessmen was highlighted at great length by the antisemite Édouard Drumont in his journal La Libre Parole. A century after the Revolution had emancipated France’s Jews, a Rothschild wedding in Paris was invaded by a mob shouting “Death to the Jews”.

These events inspired Herzl to write his play The New Ghetto in just 17 days in late 1894. Still an assimilationist when he began, his writing of the play brought a reversal in his thought, convincing him that only in a state of their own could Jews free themselves from their ‘moral ghetto’. His conversion was reinforced when he witnessed the public degradation of Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish army officer convicted of treasonous espionage (later to be exonerated).

A few months later he wrote Der Judenstaat – ‘The Jewish State’ – just as Karl Lueger was elected Mayor on an openly antisemitic platform. Lueger took office in 1897, the year of the first Zionist Congress in Basel. Modern Zionism was born.

Herzl’s Zionism went down badly in establishment Jewish circles. “Our language is German, not Hebrew,” came the protest. Although he received support from some Jewish writers, others in the Modernist movement such as Schnitzler, Freud and Kraus, along with the Chief Rabbi, were either not convinced or opposed. Many preferred to work within the Social Democratic Party to improve conditions.

Zweig, to whom Herzl was a hero, was sympathetic, yet felt unable to embrace Zionism. For many Jews, life in Vienna was just too comfortable. After Herzl died in 1904, it would be the masses of oppressed Jews in the shtetls of eastern Europe who were most enthused by his vision.

After the Great War, with the empire gone and Austria now a small republic, political and social strife intensified. But complacency would rule the attitudes of most Viennese Jews for many more years, even when events next door in Germany should have been a warning. By 1933, an Austrian-born youthful admirer of von Schönerer had become German Chancellor, calling himself ‘Führer’.

In 1938, the year of the Anschluss (union with Germany), Viennese Jews numbered some 170,000. The entry of German troops on 12 March sent them into a panic. Tens of thousands tried to flee; many committed suicide. Soon came the confiscations of property, the pogroms and humiliations. Jeering crowds took delight in watching Jewish professionals forced to their knees to scrub pavements with small brushes. The illusion of assimilation lay shattered in the broken glass of Kristallnacht.

By late 1939, about 120,000 of Austria’s Jews had managed to escape. Of the estimated 72,000 still caught in the trap, all but 7,000 would be murdered in the camps of Dachau and Mauthausen or, following deportation, in mass shootings in Poland and the occupied Soviet Union.

Zweig had left Austria during 1934, lived for a period in London and finally sailed to Brazil. There he completed his portrait of Vienna’s Jewish golden age The World of Yesterday. The day after he finished the manuscript in Rio de Janeiro, on 22 February 1942, he and his wife took their own lives.

By Dermot Meleady

Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (1942).

‘Closed Borders: The International Conference on Refugees in Evian, 1938’, https://evian1938.de/en/refugee-crisis-1938/flight-and-expulsion-of-the-jews-from-austria/

‘Herzl’s Psychodrama’, in Segula, the Jewish History Magazine (no date) https://segulamag.com/en/articles/herzls-psychodrama/

Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State: The historic essay that led to the creation of the State of Israel, ed. with introduction by Alan Dershowitz (2019).