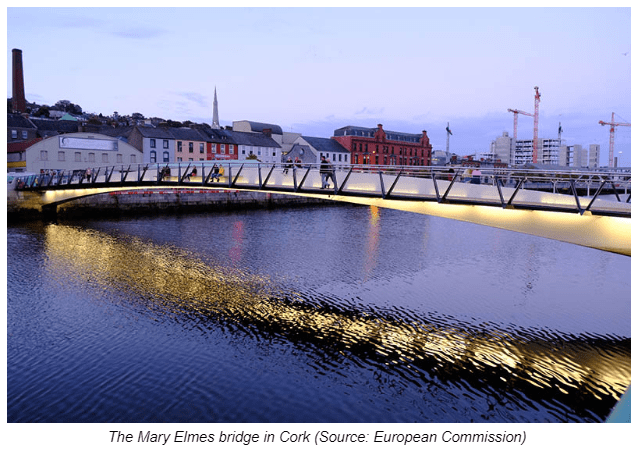

While there is ample room for everyone, there is no segregation between cyclists and pedestrians thereby requiring all users of the bridge to show a little more tolerance, patience and kindness.

It’s an understated structure. Its designers never claimed that it was going to be another iconic edifice to rival the much older Saint Patrick’s Bridge, approximately 100m upstream, never mind – for example – Dublin’s Ha’Penny Bridge. Nevertheless, as one walks west-northwest along the north side of Cork city’s bustling quays away from where the river Lee broadens out into Lough Mahon and ultimately the Celtic Sea, it provides the first chance to contemplate the river free from the noise and smell of the almost omnipresent traffic. And perhaps the person to whom this unostentatious but elegant bridge is dedicated would not have had it any other way.

Born into an era of violence

Mary Elmes was born into a Church of Ireland family in the Ballintemple district of Cork city in 1908. Her father was a pharmacist and her mother was involved in the Irish Suffragette movement, campaigning for women’s right to vote. It was her fate to be starting life in an era in which violence seemed – far too often – to be the overweening factor in the direction of the world.

She and her family were among the Corkonians who went to the quays in Cóbh to help those who had survived the torpedoing of the Lusitania by a German U-boat in May 1915. In later years, she would describe to her children what she saw that day and how those scenes had influenced the rest of her life. Five years later, during the War of Independence, the family pharmacy on Winthrop Street in Cork city centre was destroyed by British forces.

A career of academic excellence

Elmes was enrolled at Rochelle School in Cork and then attended Trinity College in Dublin where she excelled in French and Spanish Modern Literature. As a result of her success, she was awarded a scholarship in International Studies at the London School of Economics where she won a further scholarship in 1936 to continue her education at the Geneva School of International Studies in Switzerland.

However, 1936 was also the year in which the Spanish Civil War broke out. Years of polarisation and division in Spanish society finally erupted into a fratricidal conflict that lasted nearly three years. Forgoing what would surely have been a comfortable life in academia, she decided to volunteer for the Sir George Young’s University Ambulance Unit in Spain where she worked with refugees in the south east of the country. As Franco’s forces advanced over the following years, she was forced to move north with the refugees, being with the remaining numbers as they fled across the border into France

Her tireless work saved hundreds of children

Ironically, just as the Spanish Civil War was coming to an end, another far more brutal conflict was about to engulf the rest of the continent of Europe. She was still in southern France in the early 1940s when the collaborationist and antisemitic Vichy regime started to round up the Jews of southern France to deport them to death camps in eastern Europe from the Rivesaltes camp.

Documents from the time give details of how she “spirited away” nine Jewish children from the first convoy bound for Auschwitz in August 1942. She put them into the boot of her car and drove them to a children’s home in the Pyrenees. Hiding them in such children’s homes – many of which she had set up herself – her tireless work saved hundreds of French Jewish children from certain death, especially in the latter half of 1942.

‘We all experienced inconveniences’

In 1943, Elmes was detained by the Gestapo, accused of being a spy. Firstly, she was held at a military prison in Toulouse, before being sent to the Fresnes prison, near Paris. However, with the help of the Irish consulate in Vichy France and the Quaker aid organisations for whom she was working, Elmes was released after 5 months. When asked in later years about what life was like at the notorious Fresnes prison, she simply said: “Well, we all experienced inconveniences in those days, didn’t we?”

After World War II ended, she married a Frenchman from Perpignan and they had two children, Caroline and Patrick. Modest to the end of her days, she spoke little of her wartime experience, politely declining all accolades and passed away in Perpignan on March 9th 2002. On 23 January 2013, 11 years after her death, having been nominated by one of the children she rescued, she was posthumously recognised by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

She was born on this date, May 5th in 1908. Like her compatriot, Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, her story is not well known. In September 2019, her native city of Cork did recognise her contribution to humanity by opening the Mary Elmes bridge mentioned in the first two paragraphs. Her son Patrick and some of those whom she saved attended the opening.

The architects designed the bridge to be broad enough to accommodate both cyclists and pedestrians. However, there is no segregation between them, thereby requiring cyclists to cycle more slowly, pedestrians to be more careful and everyone to show a little more tolerance, patience and kindness – a fitting symbol indeed to commemorate Mary Elmes. May her memory be a blessing.

By Ciarán Ó Raghallaigh

Sources

- Mary Elmes Biography: Scholar, linguist and heroine of two wars. “The Irish Oskar Schindler”. https://hetireland.org/programmes/mary-elmes-prize/mary-elmes-biography/

- Bridge honouring the ‘Irish Oskar Schindler’ opens in Cork. https://www.rte.ie/news/munster/2019/0927/1078684-mary-elmes-bridge-cork/

- Connecting Cork – new bridge supports city’s sustainability drive. https://www.arup.com/projects/mary-elmes-bridge