The use of terms by international media outlets in their coverage of the Israel-Palestine issue has a crucial effect on how the world sees it.

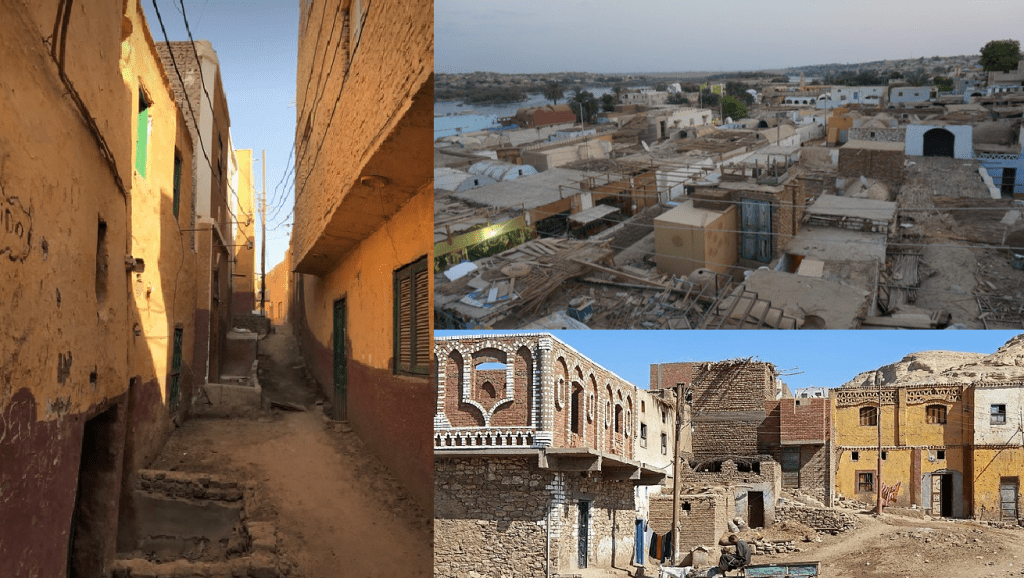

Look at the two photo-montages below and ask yourself what you see. You will probably conclude that they both depict towns in parts of the world that are somewhat poorer than most western countries but aren’t as destitute as – for example – towns in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Conditions may be a little better in the first photo-montage but in all the images depicted, the buildings are permanent, built of bricks or concrete with evidence of power lines and in the first images, satellite dishes.

Or when is a refugee camp not a refugee camp?

If that is your conclusion, then you are correct. Here’s a second question: what image comes to mind when you hear the term “refugee camp”? Probably, you’ll think of unfortunate people living in tents or other such temporary structures. As per the captions, the images below are from towns in Upper Egypt, while those in the above photo montage depict the scenes from Balata in the West Bank. Balata is a town with a population of over 30,000 people, with streets and permanent buildings that have been standing for decades. While no-one would describe any of the Egyptian towns depicted as anything other than towns, it may come as a surprise to learn that Balata is commonly referred to – not as a town but – as a “refugee camp”.

The use of terms by international media outlets in their coverage of the Israel-Palestine issue has a crucial effect on how the world sees it. Hamas and Fatah militants are more often than not referred to just as “Palestinians” or even “Palestinian civilians”. Missile attacks from Gaza resulting in an Israeli response are lazily called the “cycle of violence”, ignoring the fact that for months before the attacks from Gaza, there was no violence. And towns that have been in existence for decades with streets, houses, apartments, shops etc. are described as “Palestinian refugee camps”.

The decades-long agenda

Of course, there is a method to this madness. Arab leaders have had an agenda for decades to not regularise the situation of Palestinian Arabs who fled their homes during the 1948 war when Arabs attacked the newly independent State of Israel. Their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are to be referred to as refugees. If they’re in neighbouring Arab countries, they’re not to be granted equal rights. Also, the towns where they live are to be referred to as “refugee camps”, not “towns”.

Let’s broaden this game. By the same token, Pakistan has up to 30 million Muhajir refugees – Muhajirs being those who fled India in 1947 and their descendants. Such an assertion would be greeted with howls of laughter in Islamabad and Lahore. Likewise, southern Israeli towns such as Sderot and Netivot could be referred to as “refugee camps” as so many of their inhabitants are either Jewish refugees from Arab and Islamic countries or their descendants. Such a statement would generate incredulous and possibly angry reactions from the residents of those two towns in the Negev.

Encouraged to wallow in victimhood

Therein lies the difference between Jewish refugees and Palestinian refugees. The former moved on with their lives and helped to build one of the wealthiest and most technologically advanced countries in the world while the latter are encouraged by the international community to wallow in victimhood, with their leaders constantly saying no to all peace overtures.

So, whether you like it or not, those are the rules. Palestinian refugees inherit their refugee status (yeah, even to the third or fourth generation). Also they live in refugee camps and never in cities, towns or villages. It doesn’t matter if it looks like any other city, town or village across the Arab world; it’s still a refugee camp.

A few tents can now be a village

However, all rules have loopholes and this one does too. Take the example of Khirbet Humsa, which was never anything more than a few illegally constructed tents and shacks in a closed military zone. Somehow, as soon as the Israeli military tried taking action against it, these temporary structures were elevated to the level of a Palestinian “village” or even a “town” by anti-Israel groups. The international media parrotted this distortion, thus presenting the story with the implication that what Israel was destroying was a large, permanent community when it was nothing of the sort.

We have in the past covered the controversy about Khirbet Humsa, pointing out that the Irish army wouldn’t allow anyone to build a few tents and shacks in the Glen of Imaal. As the administering power in Judea-Samaria, Israel has the responsibility to keep some basic control on illegal structures. Bearing that in mind, and as we have pointed out in the past, the Israeli authorities take action against all such illegal buildings, including those constructed by Israelis, obviously. The international media only seem to report the issue when the illegal structures are built by Palestinian Arabs, with the implication that their removal is somehow wrong.

We are where we are

This is where we are with the use of terms to describe Palestinian communities. A town consisting of tens of thousands of people with streets, permanent buildings, residences etc. is nothing more than a “refugee camp”, suggesting that it’s basically composed of tents and shacks.

This usually happens when Israelis attempt to take action against some militant group that has launched terrorist attacks against Israelis and are ensconced in that town.The agenda is obvious: it’s presented as a community of poor, helpless people in tents – not people living in a town like any other town from Morocco to Iraq.

Meanwhile, paradoxically, a few tents and shacks built illegally in a closed military zone are a “village” or even possibly, a “town”. Such terms only enter the public domain when the Israeli authorities try to remove them.

The meaning of any word or term can be very fluid when applied to the Israel-Palestine issue. If there’s any sense to be made from the paradoxes described above, it’s that such meanings tend towards the ones that – in that particular context – portray Israel in the worst possible light. The surprise is not that this is happening; after all Israel faces a vast campaign of demonisation and distortion every hour of the day, every day of the year. The surprise is that international media outlets reliably act as a conduit for the distortion and only rarely question it.

By Ciarán Ó Raghallaigh