May his memory be a blessing and - as war and tyranny threaten Europe again - may it be a reminder to us all of the extraordinary goodness that even one human being can bring to the world.

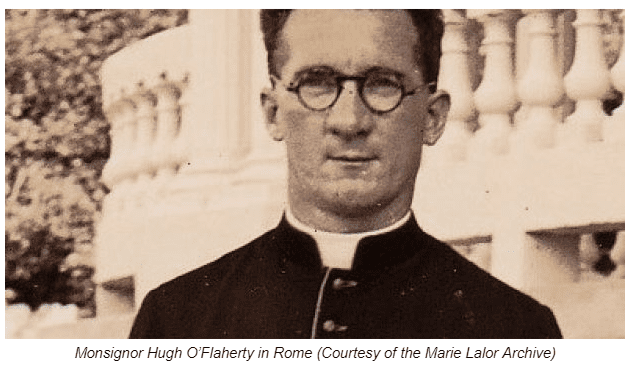

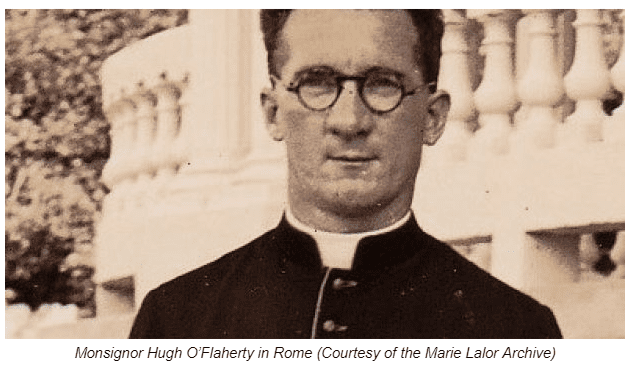

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty was one of the greatest Irish people who was ever born. However, few people know of his story. This man defied the brutal Nazi occupation of Italy in the early 1940s to save thousands of Jewish civilians and Allied soldiers from certain death.

Kerryman or Corkman?

He was actually born in Cork (so Corkonians will feel justified in claiming him too) but his parents moved to Killarney when he was still a baby. His father, James O’Flaherty, worked as a steward on the town golf course so, over time, young Hugh became an excellent golfer.

In 1918 he enrolled at a Jesuit college in Mungret, County Limerick where men planning to become Catholic missionaries were educated. His sponsor was Cornelius O’Reilly, the Irish bishop of the South African city of Cape Town. Hugh was posted to work there after his ordination.

After spending time as a Vatican diplomat in Egypt, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Czechoslovakia, he was sent to work in the Vatican with the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, a Vatican body responsible for missionary work and related activities. And it was there, in Rome, where – during the war-ravaged years of the early 1940s – that he was to engage in the most remarkable work of his life.

The Nazi horror comes to Rome

In late 1943, as the tide of war was turning against the Axis powers, Italy withdrew from its alliance with Germany. Thousands of Allied prisoners of war (POWs) were released. However, in the chaos that followed Italy’s withdrawal from the war, Germany occupied the country and the POWs were in grave danger of being captured again.

O’Flaherty organised escape routes for the allied troops and for anyone who sought refuge, including large numbers of Jews. Using a close network of trusted friends and confidantes (including priests from New Zealand, Malta, and the Netherlands), he set up safe houses all over Rome and even in the Vatican itself where his activities soon came to the attention of the Nazis, and especially, the SS leader in Italy, Herbert Kappler. Because of his work, O’Flaherty was a particular focus of the hatred of the Nazis and their Italian collaborators made no secret of their intention to capture O’Flaherty and subject him to prolonged torture before murdering him.

They can’t catch the Kerryman!

This did nothing to dissuade the Kerryman. He smuggled out Jewish people dressed as nuns and monks, he disguised partisans as Swiss guards and hid thousands of refugees in the most unusual places in the Vatican and around the city of Rome. One of the first hideouts was beside the local SS headquarters. In his book “Wherever Green is Worn”, the writer Tim Pat Coogan describes how fugitive Jews could conduct and take part in Jewish religious services in the Basilica of San Clemente as it was under Irish diplomatic protection.

Furious with the failure of his network of spies, thugs and traitors to kill O’Flaherty, Herbert Kappler became increasingly obsessed with capturing the Irishman. The Nazis recognised the Vatican as neutral so O’Flaherty was safe within the confines of the tiny area governed by the Holy See. Kappler had a white line drawn on the cobblestones at the opening to Saint Peter’s Square and the Monsignor was quietly advised via diplomatic channels that he needed to stay behind this line. To step over that line would mean arrest, torture and death. There were several attempts by the Nazis and Fascists to trick him into crossing the line but each one failed.

Cassocks and coal sacks

Nevertheless, he did have to leave the Vatican often because his work for the fugitives necessitated it. In one memorable incident, the SS raided one of the safe houses when O’Flaherty was visiting there and while he hid in the cellar, the Nazi soldiers would eventually have found him. Luckily, it just so happened that two coal-men came to deliver their supplies while the SS were still searching the house. O’Flaherty took the work clothes of one of them and walked calmly to freedom past the Nazi thugs while carrying a coal sack.

Despite the best efforts of the Nazis, O’Flaherty always managed to escape and survive, earning him the nickname of the “Vatican Pimpernel”. When the Allied forces liberated Rome, his network was still caring for nearly 4,000 fugitives including 1700 British people and nearly 1000 South Africans. This doesn’t include Jewish refugees and various other smaller groups of women and men who were under O’Flaherty’s personal protection and care.

Eulogised in book and film

O’Flaherty was portrayed by Gregory Peck in the 1983 television film, “The Scarlet and the Black”. Based on the 1967 novel “The Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican” by the writer JP Gallagher, the film tells the story of O’Flaherty’s many activities from the German occupation of Rome to its liberation by the Allies. The title of the film refers to the black cassock and scarlet sash worn by Monsignors and bishops in the Catholic Church, as well as the two main colours used by the Nazi Party.

Sadly, Monsignor O’Flaherty never got to read the novel, never mind see the film. He suffered a stroke while saying Mass in 1960 and had to return to Ireland to recuperate. He was due to be announced as the Papal Nuncio to newly-independent Tanzania. However, he never recovered and died on 30 October 1963, 65 years, 8 months and 2 days after he was born and 124 years ago today on February 28th 1898.

May his memory be a blessing and – as war and tyranny threaten Europe again – may it be a reminder to us all of the extraordinary goodness that even one human being can bring to the world.

By Ciarán Ó Raghallaigh